“The nature of the impact on performers is unique, especially with generative AI tools that can be used to recreate a performer image, likeness, or voice persona, or to do things that they didn’t originally contemplate ever doing,” says Crabtree-Ireland. “That’s a concern.”

Actors, like all Americans, are protected against commercial appropriation of their identity by the right of publicity—also known as name, image, and likeness rights. SAG wants to buttress these protections and stomp out exploitative terms like the vampire example by adding “informed consent” into future contracts: Certain kinds of AI use must be disclosed and compensated, the union argues.

But writers cannot lean on publicity rights in the same way. If they own the rights, they can seek recourse or compensation if their work is scraped by large language models, or LLMs, but only if the resulting work is deemed a reproduction or derivative of their script. “If the AI has learned from hundreds of scripts or more, this is not very likely,” says Daniel Gervais, a professor of intellectual property and AI law at Vanderbilt University.

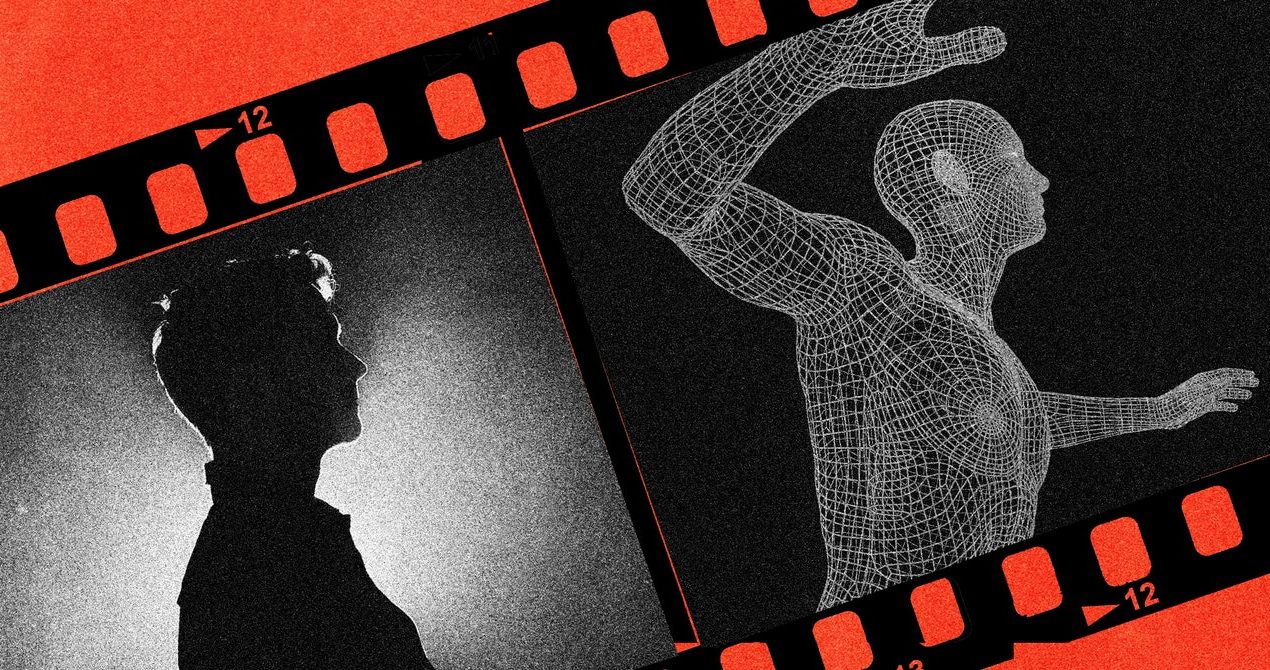

And it’s this scraping, applied to performers, that concerns talent reps. Entertainment lawyer Leigh Brecheen says she’s most worried about her clients’ valuable characteristics being extracted in a way that isn’t easily identifiable. Imagine a producer conjuring a digital performance with the piercing intensity of Denzel Washington while entirely skirting his wages. “Most negotiated on-camera performer deals will contain restrictions against the use of name, likeness, performance in any work other than the one for which they are being hired,” Brecheen says. “I don’t want the studio to be able to use the performance to train AI either.” This is why, as Crabtree-Ireland explains, it is crucial to reframe AI works as an amalgam of countless humans.

But will people care if what they’re watching was made by an AI trained on human scripts and performances? When the day comes that ChatGPT and other LLMs can produce filmable scenes based on simple prompts, unprotected writers rooms for police procedurals or sitcoms would likely shrink. Voice actors, particularly those not already famous for on-camera performances, are also in real danger. “Voice cloning is essentially now a solved problem,” says Hany Farid, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley who specializes in analyzing deepfakes.

Short term, most AI-generated actors may come off like Fake Ryan Reynolds: ghoulishly unlikeable. It seems more likely that people will accept audiobooks made by AI or a digitally rendered Darth Vader voice than a movie resting on the ripped shoulders of an AI-sculpted GigaChad-esque action hero.

Long term, though, if AI replicants escape the uncanny valley, audiences of the future may not care whether the actor in front of them is human. “It’s complicated,” says Matthew Sag, a professor of law and artificial intelligence at Emory University. “The job of writing can be encroached on in a marginal or progressive way. Performers are likely to be replaced in an all-or-nothing way.”

As the actors’ union and Hollywood studios head into talks next week, the key concern will be economic fairness: The union states that it has become increasingly difficult for guild members to “maintain a middle-class lifestyle.” There is a modern disconnect between a film or TV show’s success and residual compensation, unions argue, as well as longer gaps between increasingly shorter seasons, which means less time spent working.

In this context, AI could be Hollywood’s next gambit to produce more content with fewer humans. Like the AI-generated Reynolds, the whole thing would be banal if it wasn’t so critical. As such, union strikes remain a possibility. “They’ve got a 2023 business model for streaming with a 1970 business model for paying performers and writers and other creatives in the industry,” says Crabtree-Ireland. “That is not OK.”

Source