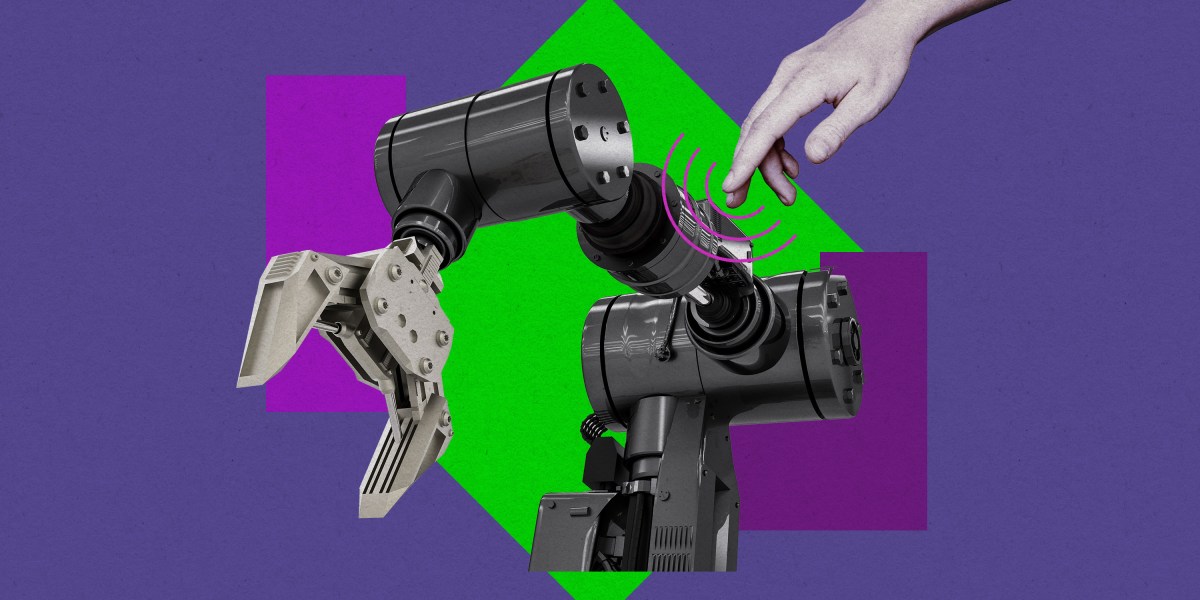

Even the most capable robots aren’t great at sensing human touch; you typically need a computer science degree or at least a tablet to interact with them effectively. That may change, thanks to robots that can now sense and interpret touch without being covered in high-tech artificial skin. It’s a significant step toward robots that can interact more intuitively with humans.

To understand the new approach, led by the German Aerospace Center and published today in Science Robotics, consider the two distinct ways our own bodies sense touch. If you hold your left palm facing up and press lightly on your left pinky finger, you may first recognize that touch through the skin of your fingertip. That makes sense–you have thousands of receptors on your hands and fingers alone. Roboticists often try to replicate that blanket of sensors for robots through artificial skins, but these can be expensive and ineffective at withstanding impacts or harsh environments.

But if you press harder, you may notice a second way of sensing the touch: through your knuckles and other joints. That sensation–a feeling of torque, to use the robotics jargon–is exactly what the researchers have re-created in their new system.

Their robotic arm contains six sensors, each of which can register even incredibly small amounts of pressure against any section of the device. After precisely measuring the amount and angle of that force, a series of algorithms can then map where a person is touching the robot and analyze what exactly they’re trying to communicate. For example, a person could draw letters or numbers anywhere on the robotic arm’s surface with a finger, and the robot could interpret directions from those movements. Any part of the robot could also be used as a virtual button.

It means that every square inch of the robot essentially becomes a touch screen, except without the cost, fragility, and wiring of one, says Maged Iskandar, researcher at the German Aerospace Center and lead author of the study.

“Human-robot interaction, where a human can closely interact with and command a robot, is still not optimal, because the human needs an input device,” Iskandar says. “If you can use the robot itself as a device, the interactions will be more fluid.”

A system like this could provide a cheaper and simpler way of providing not only a sense of touch, but also a new way to communicate with robots. That could be particularly significant for larger robots, like humanoids, which continue to receive billions in venture capital investment.

Calogero Maria Oddo, a roboticist who leads the Neuro-Robotic Touch Laboratory at the BioRobotics Institute but was not involved in the work, says the development is significant, thanks to the way the research combines sensors, elegant use of mathematics to map out touch, and new AI methods to put it all together. Oddo says commercial adoption could be fairly quick, since the investment required is more in software than hardware, which is far more expensive.

There are caveats, though. For one, the new model cannot handle more than two points of contact at once. In a fairly controlled setting like a factory floor that might not be an issue, but in environments where human-robot interactions are less predictable, it could present limitations. And the sorts of sensors needed to communicate touch to a robot, though commercially available, can also cost tens of thousands of dollars.

Overall, though, Oddo envisions a future where skin-based sensors and joint-based ones are merged to give robots a more comprehensive sense of touch.

“We humans and other animals have integrated both solutions,” he says. “I expect robots working in the real world will use both, too, to interact safely and smoothly with the world and learn.”

Article Source link and Credit