Most people take boiling water for granted. For Associate Professor Matteo Bucci, uncovering the physics behind boiling has been a decade-long journey filled with unexpected challenges and new insights.

The seemingly simple phenomenon is extremely hard to study in complex systems like nuclear reactors, and yet it sits at the core of a wide range of important industrial processes. Unlocking its secrets could thus enable advances in efficient energy production, electronics cooling, water desalination, medical diagnostics, and more.

“Boiling is important for applications way beyond nuclear,” says Bucci, who earned tenure at MIT in July. “Boiling is used in 80 percent of the power plants that produce electricity. My research has implications for space propulsion, energy storage, electronics, and the increasingly important task of cooling computers.”

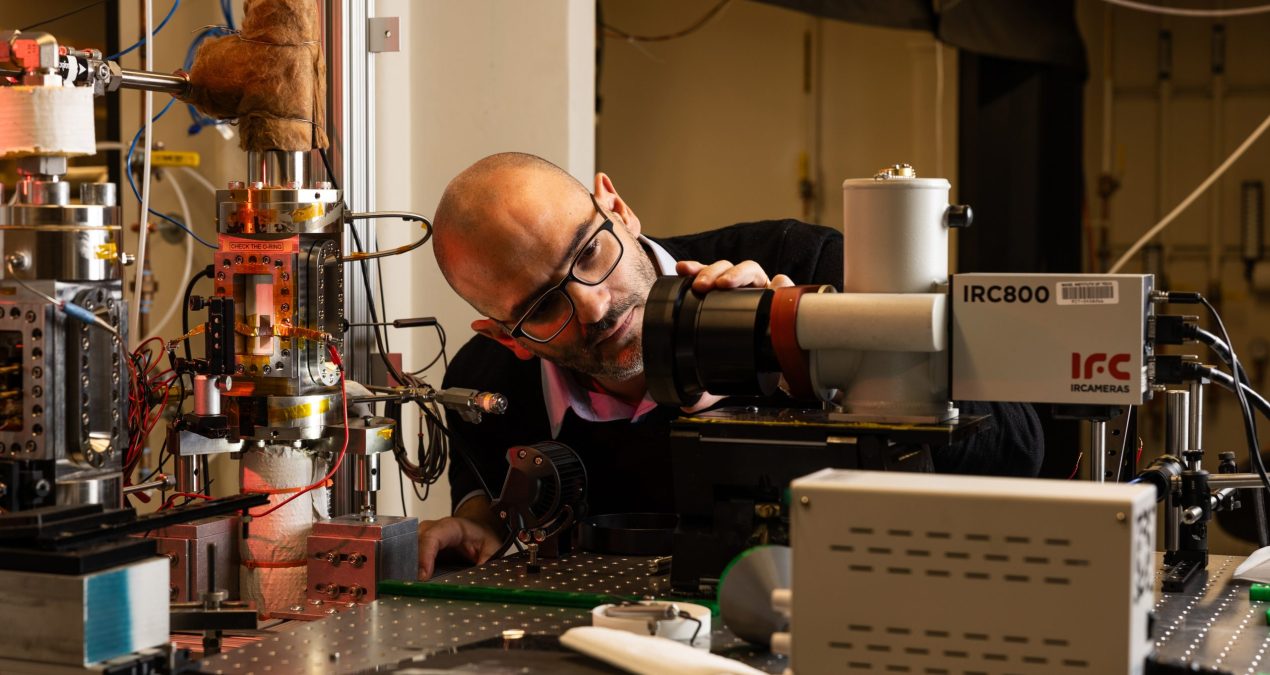

Bucci’s lab has developed new experimental techniques to shed light on a wide range of boiling and heat transfer phenomena that have limited energy projects for decades. Chief among those is a problem caused by bubbles forming so quickly they create a band of vapor across a surface that prevents further heat transfer. In 2023, Bucci and collaborators developed a unifying principle governing the problem, known as the boiling crisis, which could enable more efficient nuclear reactors and prevent catastrophic failures.

For Bucci, each bout of progress brings new possibilities — and new questions to answer.

“What’s the best paper?” Bucci asks. “The best paper is the next one. I think Alfred Hitchcock used to say it doesn’t matter how good your last movie was. If your next one is poor, people won’t remember it. I always tell my students that our next paper should always be better than the last. It’s a continuous journey of improvement.”

From engineering to bubbles

The Italian village where Bucci grew up had a population of about 1,000 during his childhood. He gained mechanical skills by working in his father’s machine shop and by taking apart and reassembling appliances like washing machines and air conditioners to see what was inside. He also gained a passion for cycling, competing in the sport until he attended the University of Pisa for undergraduate and graduate studies.

In college, Bucci was fascinated with matter and the origins of life, but he also liked building things, so when it came time to pick between physics and engineering, he decided nuclear engineering was a good middle ground.

“I have a passion for construction and for understanding how things are made,” Bucci says. “Nuclear engineering was a very unlikely but obvious choice. It was unlikely because in Italy, nuclear was already out of the energy landscape, so there were very few of us. At the same time, there were a combination of intellectual and practical challenges, which is what I like.”

For his PhD, Bucci went to France, where he met his wife, and went on to work at a French national lab. One day his department head asked him to work on a problem in nuclear reactor safety known as transient boiling. To solve it, he wanted to use a method for making measurements pioneered by MIT Professor Jacopo Buongiorno, so he received grant money to become a visiting scientist at MIT in 2013. He’s been studying boiling at MIT ever since.

Today Bucci’s lab is developing new diagnostic techniques to study boiling and heat transfer along with new materials and coatings that could make heat transfer more efficient. The work has given researchers an unprecedented view into the conditions inside a nuclear reactor.

“The diagnostics we’ve developed can collect the equivalent of 20 years of experimental work in a one-day experiment,” Bucci says.

That data, in turn, led Bucci to a remarkably simple model describing the boiling crisis.

“The effectiveness of the boiling process on the surface of nuclear reactor cladding determines the efficiency and the safety of the reactor,” Bucci explains. “It’s like a car that you want to accelerate, but there is an upper limit. For a nuclear reactor, that upper limit is dictated by boiling heat transfer, so we are interested in understanding what that upper limit is and how we can overcome it to enhance the reactor performance.”

Another particularly impactful area of research for Bucci is two-phase immersion cooling, a process wherein hot server parts bring liquid to boil, then the resulting vapor condenses on a heat exchanger above to create a constant, passive cycle of cooling.

“It keeps chips cold with minimal waste of energy, significantly reducing the electricity consumption and carbon dioxide emissions of data centers,” Bucci explains. “Data centers emit as much CO2 as the entire aviation industry. By 2040, they will account for over 10 percent of emissions.”

Supporting students

Bucci says working with students is the most rewarding part of his job. “They have such great passion and competence. It’s motivating to work with people who have the same passion as you.”

“My students have no fear to explore new ideas,” Bucci adds. “They almost never stop in front of an obstacle — sometimes to the point where you have to slow them down and put them back on track.”

In running the Red Lab in the Department of Nuclear Science and Engineering, Bucci tries to give students independence as well as support.

“We’re not educating students, we’re educating future researchers,” Bucci says. “I think the most important part of our work is to not only provide the tools, but also to give the confidence and the self-starting attitude to fix problems. That can be business problems, problems with experiments, problems with your lab mates.”

Some of the more unique experiments Bucci’s students do require them to gather measurements while free falling in an airplane to achieve zero gravity.

“Space research is the big fantasy of all the kids,” says Bucci, who joins students in the experiments about twice a year. “It’s very fun and inspiring research for students. Zero g gives you a new perspective on life.”

Applying AI

Bucci is also excited about incorporating artificial intelligence into his field. In 2023, he was a co-recipient of a multi-university research initiative (MURI) project in thermal science dedicated solely to machine learning. In a nod to the promise AI holds in his field, Bucci also recently founded a journal called AI Thermal Fluids to feature AI-driven research advances.

“Our community doesn’t have a home for people that want to develop machine-learning techniques,” Bucci says. “We wanted to create an avenue for people in computer science and thermal science to work together to make progress. I think we really need to bring computer scientists into our community to speed this process up.”

Bucci also believes AI can be used to process huge reams of data gathered using the new experimental techniques he’s developed as well as to model phenomena researchers can’t yet study.

“It’s possible that AI will give us the opportunity to understand things that cannot be observed, or at least guide us in the dark as we try to find the root causes of many problems,” Bucci says.

Source